Concurrency from single host applications up to massively distributed services

Concurrency is when multiple software threads or programs are run at the same time, and is a key aspect of many modern applications.

Web browsers run dozens of concurrent processes based on your activity, querying servers, downloading files, and executing scripts all at once.

Online services with millions of active users run a scaled up number of concurrent processes across thousands of servers, with various distributed system design patterns to support this.

This post will describe several levels of concurrency, how they’re commonly applied, and pros and cons of each approach.

Levels of concurrency

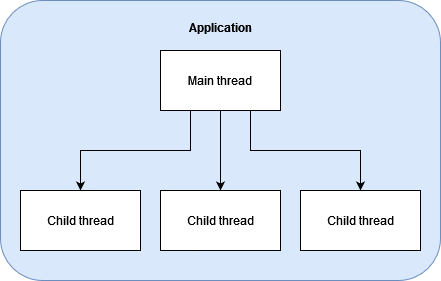

Multi-threaded applications

Within application code, we can run multiple threads concurrently.

This approach can be locally applied regardless of whether an application is run on a single host or in a distributed service. However, multi-threaded code increases code complexity and introduces thread safety issues, and an error in one thread may take down the entire application.

A common use case for multi-threading is when we need to make multiple requests to other services that may each take multiple seconds to complete. We can trigger each request in a separate thread to run them concurrently, and collect the results at the end of the longest running call, rather than synchronously making one request at a time after the prior response has returned.

Latency trade-offs

Example 1: Suppose we will run 4 requests that each take 2 seconds, 5 seconds, 5 seconds, and 1 second to complete, and each thread adds 20 milliseconds of overhead to start and close. We’ll exclude the time to combine results as equivalent between multi-threaded and synchronous approaches. Our runtime with multi-threading will be max(2, 5, 5, 1) + 0.02*4 = 5.08 seconds, compared to the synchronous approach taking 2 + 5 + 5 + 1 = 13 seconds to make all requests. In this scenario, multi-threading reduces our latency by 7.92 seconds.

Example 2: Splitting tasks into threads does not come for free and may not worthwhile for very short-lived requests. For example, if we have 1000 requests that each take 0.01 seconds to complete, running each request in a separate thread would take max(0.01) + 0.02*1000 = 20.01 seconds, compared to the synchronous approach taking 1000*0.01 = 10 seconds. In this case, the synchronous approach is twice as efficient as multi-threading.

Since the cost of such a high branching factor is high, in reality, we’ll typically break this workflow up into batches of requests per thread, such as 200 requests per thread.

Example 2b: Given 1000 requests that each take 0.01 seconds to complete, if we split the work into 5 batches of 200 requests per thread, computing all the results would take max(200*0.01, 200*0.01, 200*0.01, 200*0.01, 200*0.01) + 0.02*5 = 2.1 seconds, compared to the synchronous approach taking 1000*0.01 = 10 seconds. By batching the work before applying multi-threading, we can reduce latency compared to synchronous calls by 7.9 seconds.

Multi-threading provides the most latency reduction when we’re able to run multiple long-running tasks in parallel, especially multi-second tasks, whether each task is a single long-running request or a series of requests adding up to seconds.

Multi-container hosts

Within a host, we can run multiple containers which each receive allocated memory and run an isolated instance of application code.

![]()

This allows us to fully utilize a host’s CPU and memory, while we will eventually get to a point where the host no longer has sufficient CPU or memory capacity to add more containers, or where performance begins to drop due to increased context switching and IO bottlenecks.

Isolating concurrent applications in separate containers also improves system reliability, since regardless of individual application failures, the other containers can continue running. However, we are still vulnerable to host-level failures.

A single host can be sufficient for some small-scale services that only have a few hundred concurrent requests and are acceptable to periodically take offline for maintenance. For services that need to provide 24/7 availability or handle more traffic, we will graduate to distributed services where this host will be a single unit of a larger architecture, leading us to the multi-host cluster.

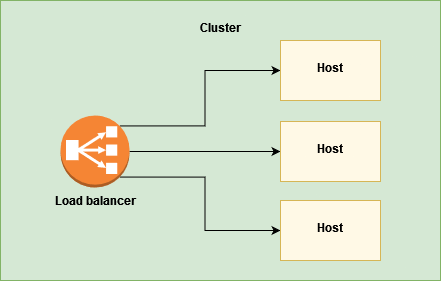

Multi-host clusters behind a load balancer

When we require high availability or more concurrency than a single host can support, we can set up a load balancer that distributes traffic across multiple hosts, forming a cluster of hosts.

This allows us to horizontally scale, that is, add or remove servers to our resource pool as needed. Horizontal scaling makes our service more robust to individual host failures and enables more flexibility in our infrastructure, allowing us to swap out different types of hosts at will, patch or update individual hosts without affecting service availability, and pay for just as many hosts as are needed to meet current demand.

This is often the go-to design pattern for services that need to process thousands of concurrent requests, which a single host may no longer be able to handle.

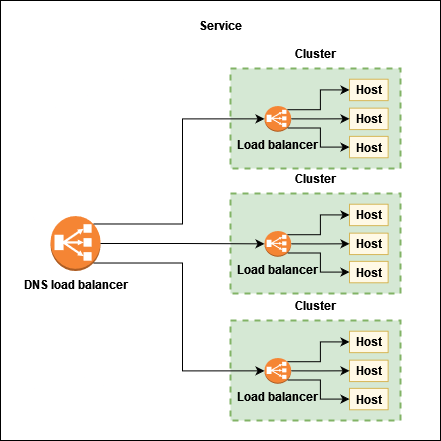

Multi-cluster services

When we have more traffic than a single load balancer can handle, we can set up a DNS load balancer to distribute traffic across multiple clusters.

This is rarely the starting point for a new service. We only want to add this level of complexity when absolutely necessary, such as when scaling up to millions of concurrent requests, or after hitting infrastructure restrictions on load balancer concurrent connections or maximum attached endpoints.

Many cloud providers provide distributed DNS load balancers that remove the single point of failure of a traditional load balancer, scale to millions of concurrent users, and automatically route traffic to the closest regional cluster.

DNS load balancer trade-offs

DNS load balancers are more limited in functionality than many specialized load balancers. For example, AWS network load balancers can support more granular access controls and security configurations, and integrate with compute services to automatically replace unhealthy hosts that fail to respond to the load balancer.

DNS also requires its connected endpoints to be accessible to the Internet, which is not always ideal. Following the security principle of defence-in-depth, when protecting critical data or infrastructure, anything that doesn’t need to be connected to the Internet, shouldn’t be. Network load balancers can be set up in protected virtual private networks to only allow access from allow-listed hosts or other trusted networks.

For these reasons, in some scenarios it will make sense to have the added complexity of both a frontend DNS load balancer to distribute traffic to the closest cluster, and backend application load balancers that provide more functionality and integration with your local infrastructure.

If you don’t need any functionality that isn’t supported by a DNS load balancer, can live with your servers being accessible from the Internet, and already manage your own health monitoring and host replacement strategy, then you can simplify your architecture by having a DNS load balancer directly route traffic to your backend servers.

Summary

We’ve discussed how concurrency can be applied at multiple levels:

- Multi-threaded applications that run multiple tasks in parallel, such as querying several websites simultaneously

- Multi-container or multi-process hosts that run multiple applications in isolation from one another, so that a given application can continue running if others fail

- Multi-host clusters that enable horizontally scaling a service to process hundreds of thousands of concurrent requests

- Multi-cluster services that enable routing traffic to local load-balanced clusters that can be independently scaled, to process millions of concurrent requests

Many distributed services now start with multi-host clusters for reliability and scalability reasons, so that any given host can be replaced without impacting customer service, and additional hosts can be added as needed.

A single load balancer and backend compute cluster can often handle hundreds of thousands of concurrent requests or more, while the load balancer may become a single point of failure for your service. Distributed DNS load balancers can help to mitigate this concern when it’s acceptable for your servers to be accessible from the Internet.

For applications where you need to handle millions of concurrent requests and have business requirements not met by a single DNS load balancer, such as needing granular access control for your backend servers or integrations with other infrastructure, a DNS load balancer in front of multiple load-balanced clusters can meet these demands with the trade-off of an additional layer of complexity.

Addendum

Before scaling your service to process millions of concurrent requests and paying hundreds of thousands of dollars to do so, make sure this is really necessary.

Would it be more efficient to extract some of your use cases to a separate microservice?

Are your hosts really doing unique work on every call? Could some of that work be deduplicated, or could the right application of a caching layer reduce your traffic and/or average latency by orders of magnitude?

Also, note that millions of concurrent users do not always translate into millions of transactions per second. If each user only needs to make a server request every few seconds, with multiple seconds between where they locally interact with rendered results, you may only have tens to hundreds of thousands of transactions per second, which while still high, lowers the required complexity of the system.

Software architecture design is an iterative process, and the optimal design will change along with the business, so it’s often worth starting with the simplest approach that meets current needs and can be scaled up or down as needed based on customer traffic. There’s no prize for building the most expensive service that no one uses.